|

|

This information you are viewing has been prepared for patients who may be facing a heart valve replacement or repair procedure. We are providing this information to help you and your loved ones learn more about the heart, how the heart valves function, how heart valve disease is diagnosed and the wide variety of treatment options available.

Please remember, this information is not intended to tell you everything you need to know about artificial heart valves or heart valve repair products, or about related medical care. Regular check-ups by a heart specialist are essential, and you are encouraged to call or see your doctor whenever you have questions or concerns about your health, especially if you experience any unusual symptoms or changes in your overall health.

The heart is a muscular organ located in the center of the chest between the lungs. Your heart is about the size of your two hands when they are clasped together. The heart is a sophisticated pump, providing blood flow to all of the cells, tissues and organs in your body. The right side of the heart pumps blood through the lungs, where the blood picks up oxygen and carbon dioxide is removed. The left side of the heart receives the oxygen-rich blood and pumps it to the rest of the body.

INSIDE YOUR HEART

|

Chambers and Valves of the Heart The heart contains four chambers. The heart pumps blood by contracting (squeezing blood out of its chambers) and relaxing (allowing blood to enter its chambers). The two upper chambers are called the atria. They receive blood returning from the body through veins. The two atria contract with only a small amount of force, sending the blood to the ventricles; the ventricles are the muscular, lower chambers of the heart. The ventricles contract with greater force, delivering blood to the body via your arteries. The right ventricle pumps blood to the lungs. Of all the chambers in the heart, the left ventricle does the greatest amount of work. Powerful contraction of the left ventricle sends oxygen-rich blood to all of the body’s organs. The heart also has four valves. Their purpose is to ensure that blood flows only in one direction. The heart’s valves open at the appropriate times to allow forward flow of blood, then close to prevent back-flow of blood. The mitral and tricuspid valves control the flow of blood from the atria to the ventricles. The aortic and pulmonic valves control the flow of blood out of the ventricles. The image below shows the chambers and valves of the heart. |

|

Circulation Through the Body

The purposes of blood are to deliver oxygen and nutrients to tissues and organs and to carry away waste products. There are actually two loops of circulation in the body

The first is a circulation loop which goes from the heart to the lungs, where blood is mixed with oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood is released. Carbon dioxide is a byproduct that the body makes when it uses oxygen. The other circulation loop goes to the body, where oxygen and other nutrients in the blood are exchanged for carbon dioxide and waste products produced by the body. Veins are the blood vessels which return blood to the heart. Arteries are the blood vessels which carry blood away from the heart to the lungs and the rest of the body.

The Heart Muscle, the Cardiac Cycle and Your Blood Pressure

The muscle of the heart (the myocardium) produces the forces necessary to eject (push) blood from the ventricles. When the ventricles contract, they force blood out of the heart through valves and into the aorta (from the left ventricle) or pulmonary artery (from the right ventricle). This phase of the heart cycle—when the ventricles are contracting and forcing blood from the heart— is called “systole."

After contracting, the ventricles must relax to receive the next volume of blood that needs to be pumped. When the ventricles relax, blood flows into them from the atria. This phase of the heart’s activity is called “diastole.’’.

|

|

|

The combination of contraction (systole) and relaxation (diastole) is called the cardiac cycle. You may have encountered these terms when your blood pressure is measured from an artery in your arm. Your blood pressure measurement includes two numbers, which correspond to systole and diastole in your cardiac cycle. For example your blood pressure may be 120 over 80. 120 is your systolic blood pressure, representing the pressure generated by contraction of your left ventricle. 80 is called the diastolic blood pressure, and is the blood pressure in your body during the time when your left ventricle is relaxed and receiving blood.

The Heart’s Arteries

Like every other organ or muscle in the body, the heart has arteries that carry blood nutrients and oxygen. The heart’s arteries are called the coronary arteries. The three coronary arteries are the right coronary artery, the left anterior descending coronary artery, and the circumflex coronary artery. When these arteries become narrowed by build-up of cholesterol-containing plaque, a person is said to have coronary artery disease. If a coronary artery becomes completely blocked, a portion of the heart muscle is deprived of its blood supply, and a heart attack occurs. A heart attack causes damage to the heart muscle as some muscle cells die.

Normal, Healthy Heart Valves

Human heart valves are remarkable structures. These tissue-paper thin flaps, or leaflets, attached to the heart wall undergo a constant “beating” as they open and close with each heart beat, day after day, and year after year. With each beat, the valves display their remarkable strength and flexibility.

There are four cardiac valves. Two of the valves are referred to as the atrioventricular (AV) valves. They control blood flow from the atria to the ventricles. The AV valve on the right side of the heart is called the tricuspid valve; it sits between the right atrium and the right ventricle. The name “tricuspid” refers to the three leaflets making up the valve. The AV valve on the left side of the heart is called the mitral valve; the mitral valve controls blood flow between the left atrium and left ventricle. It has two leaflets. The other two cardiac valves, i.e., the aortic and pulmonic valves, each have three leaflets. They are outflow valves, regulating the flow of blood as it leaves the ventricles and the heart. The aortic valve serves as the “door” between the heart and the rest of the body. Every drop of blood ejected by the left ventricle must pass through the aortic valve. The aortic valve is located between the left ventricle and the ascending aorta, or upper portion of the aorta. The pulmonic valve is located between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. The mitral and tricuspid valves are substantially larger than the aortic and pulmonic valves.

The image below shows the shape and location of the four heart valves. The characteristic heart sounds (“lubb-dubb”) are caused by the closing of the heart valves; the first by closure of the mitral and tricuspid valves and the second by closure of the aortic and pulmonic valves.

|

|

Function of Heart Valves

A normal, healthy valve would be one which minimizes obstruction and allows blood to flow freely in only one direction. It would close completely and quickly, not allowing much blood to flow back through the valve (backward flow of blood across a heart valve is called “regurgitation”). While a small amount of regurgitation, or leak, may be present and is well tolerated, severe regurgitation is always abnormal.

When a heart valve opens fully and evenly, blood flows through the valve in a smooth and even manner. When a valve does not open fully or evenly, blood flow through it becomes chaotic and turbulent. When a valve is narrowed or does not open fully, it is said to be “stenotic.”

Both regurgitation (a leak) and stenosis (a narrowing) increase the heart’s workload.

|

|

Heart valves can fail by becoming narrowed (stenotic) so that they block the flow of blood or leaky (regurgitant) so that blood flows backward in the heart. Sometimes a valve is both stenotic and regurgitant. A variety of conditions can cause these heart valve abnormalities.

Causes of Heart Valve Disease

Degenerative valve disease – This is a common cause of valvular dysfunction. Most commonly affecting the mitral valve, it is a progressive process that represents slow degeneration from mitral valve prolapse (improper leaflet movement). Over time, the attachments of the valve thin out or rupture, and the leaflets become floppy and redundant. This leads to leakage through the valve.

To know more about mitral regurgitation, go to the video click on the link

|

|

Calcification due to aging – Calcification refers to the accumulation of calcium on the heart’s valves. The aortic valve is the most frequently affected. This build-up hardens and thickens the valve and can cause aortic stenosis, or narrowing of the aortic valve. As a result, the valve does not open completely, and blood flow is hindered. This blockage forces the heart to work harder and causes symptoms that include chest pain, reduced exercise capacity, shortness of breath and fainting spells. Calcification comes with age as calcium is deposited on the heart valve leaflets over the course of a lifetime.

To know more about aortic stenosis go to the video , click on the link

|

|

Coronary artery disease – Damage to the heart muscle as a result of a heart attack can affect function of the mitral valve. The mitral valve is attached to the left ventricle. If the left ventricle becomes enlarged after a heart attack, it can stretch the mitral valve and cause the valve to leak.

Rheumatic fever – Once a common cause of heart valve disease, rheumatic fever is now relatively rare in most developed countries. Rheumatic fever is caused by an infection of the Group A Streptococcus bacteria and can detrimentally affect the heart and cardiovascular system, especially the leaflet tissue of the valves. When rheumatic fever affects a heart valve, the valve may become stenotic, regurgitant or both. It is common for the heart valve abnormality to become apparent decades after the bout of rheumatic fever.

Congenital abnormalities – Congenital heart defects (present at birth) can affect the flow of blood through the cardiovascular system. Blood can flow in the wrong direction, in abnormal patterns, and can even be blocked, partially or completely, depending on the type of heart defect present. Ranging from mild defects such as a malformed valve to more severe problems like an entirely absent heart valve, congenital heart abnormalities require specialized treatments.

Bacterial endocarditis – Bacterial endocarditis is a bacterial infection that can affect the valves of the heart causing deformity and damage to the leaflets of the valve(s). This usually causes the valve to become regurgitant, or leaky, and is most commonly seen in the mitral valve.

Diagnosis of Valve Disease

Before a patient sees a primary care physician or a cardiologist (a doctor who specializes in understanding the heart) concerning a heart valve problem, he or she has often experienced some type of physical sign or discomfort. Some physical signs of heart valve disease include: angina (chest pain), tiredness, shortness of breath, lightheadedness or loss of consciousness.

However, in some cases a heart valve problem may cause no symptoms at all. These heart valve issues can often be identified by use of a stethoscope on routine physical examination. Heart valve abnormalities, whether stenosis or regurgitation, often produce a heart murmur. A heart murmur, particularly if it is new or loud, should prompt further investigation by your physician.

Cardiologists and surgeons have many ways of diagnosing heart valve disease. The most important is the echocardiogram.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is a special application of ultrasound that enables the cardiologist to observe the function of your heart valves and the contractions of your heart muscle. During an echocardiogram, ultrasound waves are projected onto the heart. The reflected ultrasound is “captured” by a transducer, and a computer translates the sound waves into an image. Most echocardiograms are performed by placing the ultrasound probe on a person’s chest. This is called a “transthoracic” or “surface” echocardiogram. This test is non-invasive and takes only a few minutes.

In some cases, a tranesophageal echocardiogram is performed. With this type of echocardiogram, the ultrasound probe is inserted into the esophagus through the mouth. Because the esophagus is very close to the back of the heart, this sort of echocardiogram provides excellent images of the heart and its valves.

Catheterization

Cardiac catheterization (angiography) helps to determine the function of the coronary arteries and the heart valves. Cardiac catheterization is the process by which a tube is inserted into the blood vessels and/or heart. The tube injects a contrast medium (dye) which is then visualized with X-rays. Coronary angiography is particularly useful for analyzing the coronary vessels of the heart. Most patients have a coronary angiogram, or cardiac catheterization, before heart valve surgery; this is necessary to determine whether any blocked coronary arteries require treatment at the time of surgery.

Chest X-ray

A chest X-ray can be important in the detection of calcium deposits in the heart, such as on heart valves. It will also show the size and shape of the heart and lungs. All patients will have a chest X-ray before heart valve surgery.

Diseased heart valves can be addressed in several ways. These include: 1) medication; 2) surgical valve repair; 3) surgical valve replacement; and 4) transcatheter valve replacement. While medication cannot correct valve dysfunction, it can alleviate symptoms in many cases. If repair or replacement becomes necessary, your cardiologist, surgeon or interventional cardiologist, will discuss the options with you. The choice between replacement or repair will depend on a number of factors, including the specific valve in question, the severity of the condition and whether the issue is stenosis or regurgitation.

Your Heart Team

If you will be undergoing a heart valve repair or replacement procedure, you will be cared for by a team of medical specialists who are committed to ensuring your safety and comfort before, during, and after, your procedure. Below you will find information describing different health care professionals you may meet during the course of your care.

Primary care physician — May be the first to identify the symptoms of heart valve disease or conditions that can cause heart valve disease or defects. He or she may order special tests to confirm the diagnosis or refer you to the appropriate specialist.

Cardiologist — A physician who specializes in diseases of the heart. The cardiologist does not perform heart surgery but often performs diagnostic studies to identify the cause of heart problems and determine the course of treatment to manage heart disease. The cardiologist may prescribe medications and/or refer you to a cardiovascular surgeon.

Cardiovascular surgeon — A physician who specializes in heart surgery, including the repair or replacement of diseased heart valves. The surgeon will help in the decision making process about timing and best course of action, including approach and device choice for your valve disease.

Interventional cardiologist — A physician who has additional specialized training to perform catheter-based procedures to treat heart diseases. The interventional cardiologist will work with the surgeon to determine the right candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacements.

Anesthesiologist — The anesthesiologist (doctor) or anesthetist (nurse) are trained to provide sedation or general anesthesia (sleep) during interventional procedures.

Critical care physicians and nurses — The critical care or intensive care unit is a specialized area in a hospital where you are closely monitored and treated after most interventional procedures. Working with your surgeon and/or cardiologist, the critical care team physicians and nurses manage your care during this time.

Surgical Approaches for Heart Valve Disease

Most heart surgery is performed through an incision across the full length of the breast bone, or sternum. This incision is called a median sternotomy. It generally heals quite well, with the bone requiring about 6 weeks for complete healing.

In selected patients, heart valve surgery can be performed using smaller, or minimally invasive, incisions. Smaller incisions may provide some benefit to patients. Preoperative studies, including a coronary angiography, echocardiography and, in many cases, chest CT (CAT) scan, help to determine which patients are candidates for minimally invasive surgery. These surgical approaches with small incisions also include use of the heart lung machine as do full sternotomy operations.

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR): A Less Invasive Option to Open Heart Surgery

For people who have been diagnosed with severe aortic stenosis and who are moderate or greater-risk for open heart surgery, another option is available—transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). This procedure can also be referred to as transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). It is a less invasive procedure that does not require open heart surgery.

|

|

The TAVR procedure allows a new valve to be inserted with your diseased aortic valve. The new valve will push the leaflets of your diseased valve aside. The frame will use the leaflets of your diseased valve to sure it in place. |

This less invasive procedure is different than open heart surgery. TAVR uses a catheter to replace the heart valve instead of opening the chest and completely removing the diseased valve.

The TAVR procedure can be performed through multiple approaches, how the most common approach is the transfemoral approach (through an incision in the leg). Only a Heart Team can decide which approach is best, based on a person's medical condition and other factors. Please consult a Heart Team for more information on TAVR and its associated risks

Surgical Valve Replacement

If the cardiovascular surgeon chooses to replace the patient’s heart valve, the first step is to remove the diseased valve (excise the valve and calcium deposits) and then implant a prosthetic heart valve in its place. Prosthetic valves used to replace diseased natural valves are made from a variety of materials and come in a variety of sizes.

There are two broad categories of prosthetic heart valves that are used to replace diseased valves:

- Bioprosthetic or tissue valves made primarily from animal tissue [i.e., bovine (cow) pericardium (the tough sac surrounding its heart), a porcine (pig) aortic valve, or human valves taken from cadavers]

- Mechanical valves constructed from synthetic material, primarily carbon.

Tissue Valves (Bioprosthetic Valves)

There are a wide variety of tissue valves:

- Heterograft (or Xenograft) - valves or pericardial tissue harvested from medical-grade animals (i.e., bovine (cow) or porcine (pig))

- Homograft (or Allograft) - human valves taken from cadavers.

- Autograft/Autologous tissue – normal valve that has been transferred from one position to another replacing a diseased valve within the same individual (confined to a pulmonic valve used to replace an aortic valve).

A heterograft is a biological valve made from animal tissue. For example, pericardial valves traditionally contain leaflets made from bovine (cow) pericardium (the sac surrounding its heart) and are sewn onto a flexible or semi-flexible frame. Another type of tissue valve is a porcine valve. A porcine valve is made from pig’s aortic heart valve and is usually sewn onto a flexible or semiflexible frame to make a “stented” valve; alternatively, the natural porcine aortic root is left intact to function as the frame to make a “stentless” valve. Each valve is surrounded by a cloth sewing ring. Sutures are placed through this sewing ring to secure the valve to the heart.

|

|

|

| Biological Prosthetic Heart Valves"NeoCor" |

Mechanical Valves

Mechanical valves include leaflets that are made out of a special type of carbon. These valves usually have two leaflets. The leaflets open and close during the cardiac cycle, ensuring flow of blood in one direction.

|

|

Criteria and Selection of Heart Valves

The choice between a mechanical and tissue valve depends upon an individual assessment of the benefits and risks of each valve and the lifestyle, age and medical condition of each patient.

Tissue valves do not require long-term use of blood thinners (anticoagulants). This is an important consideration for those who cannot take blood thinners because of a previous history of major bleeding (e.g., gastrointestinal or genitourinary) or an increased risk of traumatic injury and bleeding related to recreational activity, sports, or advanced age. Tissue valves generally last at least 10 years and, in some people, have lasted longer than 30 years. If a patient under 60 years of age receives a tissue valve, there is a high probability that he or she will require another valve replacement at some point; whereas, most patients who are 70 years and older do not.

Mechanical valves rarely wear out. However, they require daily treatment with blood thinners, and blood thinners can require changes in diet or activity levels.

The decision to choose a tissue or mechanical valve replacement is often related to the patient’s age, with older patients preferentially receiving tissue valves. However, there is no clear agreement on the precise age cutoff where a tissue valve may be preferable to a mechanical valve.

Valve Repair

When possible, it is generally preferable to repair a patient’s valve rather than to replace it with a prosthetic device. Valve repair usually involves the surgeon modifying the tissue or underlying structures of the mitral or tricuspid valves.

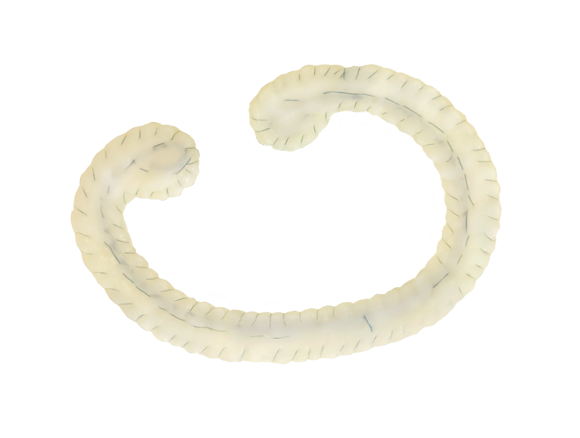

Nearly all valve repairs include placement of an annuloplasty ring or band. This is a cloth-covered device that is implanted around the circumference, or annulus, of the mitral or tricuspid valve. It provides support to the patient’s own valve and brings the valve leaflets closer together, potentially reducing leaks across the valve. There are a variety of different annuloplasty devices. The surgeon will choose one that best fits your heart valve.

|

|

|

| Biologic Mitral Valve Annuloplasty Ring"NeoCor" |

In addition to an annuloplasty, mitral valve repair frequently requires correction of problems with the leaflets or chords, which attach the valve leaflets to the heart. When a mitral valve leaks because of mitral valve prolapse, fixing the leaflets and chords (and adding an annuloplasty ring or band) restores normal valve function.

Care After a Heart Valve Procedure

The normal recovery period from standard heart valve surgery requires four to eight weeks. Recovery may be faster when a smaller incision is employed, for example, with minimally invasive and transcatheter procedures. During this time, patients gradually gain energy and resume normal activities of daily living. Regular check-ups by a heart specialist are essential, and you are encouraged to call or see your doctor whenever you have questions or concerns about your health, especially if you experience any unusual symptoms or changes in your overall health.

Diet and Exercise

Two additional important aspects of recovery and general wellness are maintenance of a healthful diet and regular exercise. If your doctor has recommended a special diet, it is important that it be followed. Healthy eating is an important part of a healthy life. During recovery, nutritious food gives your body energy and can help you heal more quickly.

To improve overall cardiovascular fitness, it is recommended that you combine a balanced diet with your doctor’s recommendations about exercise and weight control. Following a regular exercise program is an important part of maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Under your doctor’s guidance, you should gradually build up your exercise and activity level. Before you begin a new sports activity, check with your doctor.

Anticoagulants – It is important to follow your doctor’s directions for taking medications, especially if an anticoagulant has been prescribed. Anticoagulants, or blood thinners, decrease the blood’s natural ability to clot. If you must take anticoagulant drugs, you will need periodic blood tests to measure the blood’s ability to clot. This test result helps your doctor determine the amount of anticoagulant you need. It may take a while to establish the right dosage of this drug for you, but consistency and working with your doctor are important. Home testing may also be available, so check with your physician about this option. Consult your doctor about interactions with any other drugs you may be taking and dietary restrictions you may have while taking anticoagulants, and also ask about any signs to watch for that might indicate your dosage is too high.

Other Health Information – Before any dental work, including teeth cleaning, endoscopy or surgery is done, tell your dentist or doctor about your prosthetic heart valve. Patients with a valve implant are more susceptible to infections that could lead to future heart damage. Therefore, it may be necessary to take antibiotics before and after certain medical procedures to reduce the risk of infection.

Furthermore, when traveling for more than a few days, try to maintain diet and exercise level as close to normal as possible. Be sure to discuss all your medicines (including over-the-counter medicines) with your doctor, and don’t change the dosage unless instructed to.

- What is a heart valve?

Your heart has four valves: the mitral valve and the aortic valve on the left side of your heart and the tricuspid valve and the pulmonic valve on the right side of your heart. In order for blood to move properly through your heart, each of these valves must open and close properly as the heart beats. The valves are composed of tissue (usually referred to as leaflets or cusps). This tissue comes together to close the valve, preventing blood from improperly mixing in the heart’s four chambers (right and left atrium and right and left ventricle).

- When do the heart valves open and close?

You may notice that the beating of your heart makes a “lubb-dubb, lubb-dubb” sound. This sound corresponds to the opening and closing of the valves in your heart. The first “lubb” sound is softer than the second; this is the sound of the mitral and tricuspid valves closing after the ventricles have filled with blood. As the mitral and tricuspid valves close, the aortic and pulmonic valves open to allow blood to flow from the contracting ventricles. Blood from the left ventricle is pumped through the aortic valve to the rest of the body, while blood from the right ventricle goes through the pulmonic valve and on to the lungs. The second “dubb,” which is much louder, is the sound of the aortic and pulmonic valves closing.

- How often do my heart valves open and close?

The average human heart beats 100,000 times per day. Over the life of an average 70-year-old, that means over 2.5 billion beats.

- How big are my heart valves?

Your heart is about the size of your two hands clasped together. The aortic and pulmonic valves are about the size of a quarter or half dollar, while the mitral and tricuspid valves are about the size of an old-fashioned silver dollar.

- What causes valvular heart disease?

There are several reasons that one or more of your heart valves may not work properly. The ultimate effect of a diseased heart valve is that it interrupts normal blood flow through the heart. Causes may include the following:

Endocarditis

– an infection of the valve tissue.

Rheumatic fever

– a specific type of infection more prevalent in developing countries where the valve tissue becomes inflamed and/or fused together.

Calcification

– over time, calcium in your body can build up on the tissue of your valves making it difficult for them to move properly.

Congenital defects

– a condition you are born with such as having only two leaflets on the aortic valve rather than three.

Ischemia

– also known as coronary artery disease, in which the heart’s own blood vessels become clogged and can no longer deliver the proper amount of blood.

Degenerative disease

– a progressive process that represents slow degeneration from mitral valve prolapse (improper leaflet movement). Over time, the attachments of the valve thin out or rupture and the leaflets become floppy and redundant.

- How is valvular heart disease treated?

There are different methods for treating valvular heart disease, and you should discuss your options with your physician. In some cases, no action may be needed and a “wait and see” approach may be used. Your doctor may also prescribe various medications that may improve your symptoms. If the disease has progressed, your doctor may recommend intervention. What procedure is appropriate is a decision that your doctor will make in consultation with you. This is dependent upon such things as which valve or valves need to be addressed, your specific medical conditions, and other factors. In general, there are two options to treat valvular heart disease: one is to repair your native valve, and the other is to replace your native valve with a prosthetic valve.

- What are my surgical options?

During typical “open-chest” surgery to repair or replace a heart valve, the surgeon makes one large main incision in the middle of the chest and breastbone to access the heart. A heart-lung machine takes over the job of circulating blood throughout the body during the procedure, because the heart must be still and quiet while the surgeon operates. Many surgeons are now able to offer their patients minimal incision valve surgery as an alternative to open-chest heart valve surgery. Smaller incisions may be on the side of the chest or in the center. In addition, for some patients it is possible to replace the aortic valve using less-invasive, catheter-based techniques. With these approaches, an interventional cardiologist guides a new valve or a repair device into the beating heart using guidance from X-ray and echocardiography. For example, a new valve may be inserted through an incision in the leg (or slightly higher up) that does not require the chest to be opened, and cardiopulmonary bypass or use of the heart-lung machine is usually not required.

- How is minimal incision valve surgery performed?

Minimal incision valve surgery does not require a large incision or cutting through the entire breastbone. The surgeon gains access to the heart through smaller, less visible incisions (sometimes called “ports”) that are made between the ribs or a smaller breastbone incision. The diseased valve can be repaired or replaced with the surgeon looking at the heart directly or through a small, tube-shaped camera.

- How can my heart valve be repaired?

In some cases, it is possible to repair your valve. Repair is most commonly performed on the mitral and tricuspid valves. The goal of the repair procedure is to fix your native valve so that it can open and close properly, thereby restoring normal blood flow through the heart. An implantable device which is usually ring-shaped with a metal core may be placed directly above your valve and tied in place with sutures. This procedure is called ring annuloplasty. The ring helps your valve maintain its proper shape so that blood does not leak out as the heart contracts and relaxes. This surgery can be performed with a conventional, full open-chest or through a less invasive or minimal incision approach as well.

- How can my heart valve be replaced?

If your heart valve cannot be repaired, your doctor may decide to replace your native valve with a prosthetic valve. The aortic valve is the most commonly replaced heart valve. The prosthetic valves are usually one of two types: a mechanical valve or a tissue valve. A mechanical valve is made from synthetic (manmade) materials, primarily carbon. A tissue valve is usually made from either the tissue from a pig’s aorta or the tissue from the pericardium (sac surrounding the heart) of a cow. Valve replacement can be performed with a conventional, full open-chest or through less invasive or minimal incision approaches as well.

- Are there any complications or other risks with heart valve surgery that I should know about?

Serious complications, sometimes leading to re-operation or death, may be associated with heart valve surgery. It is important to discuss your particular situation with your doctor to understand the possible risks, benefits, and complications associated with the surgery.

- How long does an artificial heart valve last?

Longevity of an artificial tissue valve depends on many patient variables and medical conditions. This makes it impossible to predict how long a valve or repair device will last in any one patient. All patients with prosthetic heart valves should have a yearly echocardiogram and check-up in order to assess heart valve function.

- Should I have a mechanical valve or a tissue valve?

You should discuss this question with your doctor as there are advantages and disadvantages to both. The key is to choose the valve that best fits your lifestyle and your goals. A mechanical valve may last longer than a tissue valve (which can wear out over time). However, patients with mechanical valves are required to be on anticoagulants (blood thinners) for life. Tissue valves do not require you to be on blood thinners for the rest of your life. However, they can wear out over time which may require a re-operation.

- Should I expect an immediate improvement in my health following heart valve repair or replacement surgery?

The results of valve repair or replacement surgery vary for each individual. Many individuals feel relief from symptoms immediately, while other patients begin to notice an improvement in their symptoms in the weeks following surgery. Your doctor can help you to evaluate your progress and physical health following valve repair or replacement surgery.

- How long after heart valve repair or replacement surgery can I resume “normal” levels of activity?

If you have a valve replaced or repaired, the normal recovery period is four to eight weeks, although minimally invasive approaches are often associated with more rapid recovery. Your ability to return to your normal daily activities depends on several factors, including the type of valve repair/replacement you’ve had, how you feel, how well your incision is healing, and the advice of your doctor. Regardless of the pace of your recovery, a supervised cardiac rehabilitation program is always helpful to regain energy and ensure overall good health.

- Will I need to take any medications following my heart valve repair or replacement surgery?

As with any surgical procedure, you may be required to take medications following surgery. Discuss with your doctor which (if any) medications you may need, in particular if you received a mechanical valve which requires anticoagulants (blood thinners).

- What do I need to know if I am required to take blood thinners after my surgery?

Anticoagulants, or blood thinners, decrease the blood’s natural ability to clot. If you must take anticoagulant drugs, you will need periodic blood tests to measure the blood’s ability to clot. This test result helps your doctor determine the amount of anticoagulant you need. It may take a while to establish the right dosage of this drug for you, but consistency and working with your doctor are important. Home testing may also be available, so check with your physician about this option. Consult your doctor about interactions with any other drugs you may be taking and dietary restrictions you may have while taking anticoagulants, and also ask about any signs to watch for that might indicate your dosage is too high.

- How do I take care of my valve?

Be sure your dentist and doctors know that you have had heart valve surgery. Ask your dentist and doctor about taking antibiotics before dental or surgical procedures or endoscopy to help prevent valve infection. Always follow your doctor’s instructions carefully.

angiogram – x-ray image of an artery or a vein filled with contrast media; a diagnostic procedure is generally referred to as an angiogram.

angioplasty – the use of an inflatable balloon catheter to internally dilate a narrowed blood vessel.

anticoagulant – a drug which prevents the clotting of blood

aortic valve – the valve between the left ventricle and the aorta.

arteries – blood vessels which carry blood away from the heart

atrioventricular valve – valve between each atrium and ventricle (tricuspid and mitral valves)

atrium – the upper receiving chambers of the heart

calcification – calcium present in the blood may collect and deposit calcified masses in body tissues, such as the leaflets of heart valves, which reduce the flexibility of the leaflets

cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) – a machine used during certain surgical heart procedures that takes over the function of your heart and lungs on a temporary basis. Also called the heart-lung machine.

catheter – a tube, either flexible or non flexible, that is used to add, remove or transfer fluids or instruments used in minimally invasive procedures.

catheterization – to insert a slender tube into a body passage, vessel or cavity

commissures – regions where the individual valve leaflets come together

congenital – existing from time of birth

deoxygenated – free of oxygen.

diastole – period of the cardiac cycle when the heart relaxes to allow blood flow into the ventricles.

echocardiography – ultrasonic waves directed through the chest wall to graphically record the position and motion of the heart walls, valves and internal heart structures.

electrocardiography – a tracing showing the changes in electric activity associated with contractions of the heart

endocarditis – inflammation or infection of the lining of the heart and valve leaflets

endovascular – vascular procedures performed using (minimally invasive) catheter-directed techniques from within blood vessels.

fibrillation – rapid irregular contractions of the heart

hypertrophy – a considerable increase in the size of an organ or tissue

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – a diagnostic test that uses a magnetic field to transmit signals from the hydrogen ions in your body. These are processed through a computer and produce a tissue image, often without the use of a contrast medium.

minimally invasive procedures – procedures that can be performed through small incisions that usually result in more rapid patient recovery.

mitral valve – the valve that separates the left atrium from the left ventricle

myocardial infarction – death of myocardial tissue, usually resulting from a disruption in oxygen supply to the tissue. Also called a heart attack.

myocardium – the muscle of the heart

oxygenated – combined with oxygen

pericardial valve – tissue valve made from bovine (cow) pericardial tissue

porcine valve – tissue valve made from a pig’s aortic valve

pulmonary valve – the valve between the right ventricle and pulmonary artery

regurgitation – backward flow of blood

sinus rhythm – when the heart contracts in a normal, coordinated manner. Also called “normal sinus rhythm.”

stenosis – narrowing of an opening

superior and inferior venae cavae – the two largest veins in the body, returning deoxygenated blood to the right side of the heart

systole – period of contraction in the cardiac cycle when the ventricles in the heart squeeze or pump

transcatheter heart valve – a tissue heart valve that is compressed on a balloon catheter. The valve can be pushed through your blood vessel from a cut in your leg. The new valve is expanded within your diseased valve. The new valve will push the leaflets of your diseased valve aside.

transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) – echocardiography provides your doctor with moving pictures of your heart and heart valves so he or she can assess their function. In a TTE, a probe is placed on your chest to provide this image.

transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) – echocardiography provides your doctor with moving pictures of your heart and heart valves so he or she can assess their function. In a TEE, a probe is placed down your throat into your esophagus to provide your doctor with a more detailed picture of your heart and heart valves.

tricuspid valve – the valve that separates the right atrium from the right ventricle

ultrasound – very high-frequency sound waves which are “bounced off” structures and moving blood to obtain images and flow signals.

veins – blood vessels that return blood to the heart

ventricle – the large lower pumping chambers of the heart